India doesn’t have a single regional integration plan that excludes Bangladesh, thus making Dhaka the most prized of New Delhi’s neighborhood partners. This analysis will highlight the institutional integration dependency that India has on Bangladesh, while the second part will raise awareness about how Bangladesh can leverage this state of affairs to its benefit against India and reverse the power relations between them.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about the improving relations between India and Bangladesh, with Kolkata-based research scholar Saikat Bhattacharyya convincingly arguing that Dhaka has become subordinated to New Delhi. That’s indeed the case, and the reason for it isn’t just India’s pursuit of pure power, but its ambition to integrate the Greater South Asian region under its leadership.

Contents

India doesn’t have a single regional integration plan that excludes Bangladesh, thus making Dhaka the most prized of New Delhi’s neighborhood partners. This analysis will highlight the institutional integration dependency that India has on Bangladesh, while the second part will raise awareness about how Bangladesh can leverage this state of affairs to its benefit against India and reverse the power relations between them.Bangladesh Is India’s Most Important NeighborIndia has sought to lead or co-chair four separate regional integration frameworks, all of which include Bangladesh, but only one of the plans has the full participation of each institutional member and any realistic chance of resulting in tangible multilateral benefits:SAARCThe South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) stretches from Afghanistan to Bangladesh and also includes the island nations of the Maldives and Sri Lanka. The idea behind it is innocent enough – to provide a platform of multifaceted integration between all of the former British colonies and one-time dependent territories to integrate with one another – but its execution has been utterly flawed due to India’s politicization of the organization as an instrument of international pressure against Pakistan. New Delhi sabotaged last year’s planned meeting in Islamabad by pressuring the other members to abstain from participating, though as the author wrote at the time, “India Just Split Up SAARC And Brought The New Cold War To South Asia”, but that “The Death Of SAARC Gave Birth To ‘Greater South Asia’”.For all intents and purposes, so long as the ruling Modi-Doval Hindutva clique remains in control of India’s permanent military, intelligence, and diplomatic bureaucracies (the “deep state”), then there aren’t any realistic prospects for the SAARC format to return to being an apolitical vehicle for regional integration. Pakistan has accordingly prioritized its engagement with the Mideast and Central Asia in response, just as India has sought to do the same with ASEAN. As per the latter, New Delhi has three plans to fall back on, but only one of them has any feasible prospects for success nowadays.BCIMThe Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Corridor was supposed to be a grand cooperative undertaking between the world’s two most populous countries, China and India, but it’s regrettably underperformed in its vast potential due to New Delhi stalling the entire process. The Indians are overly afraid that China could flood their markets with all sorts of goods that would put their domestic producers out of business, hence why they prefer to keep the BCIM as more of a symbolic project than a substantial one. This has dissatisfied the Chinese, who genuinely want to bring together their and India’s economic complementarities in order to construct a win-win system of complex interdependency akin to the “Chimerica” concept.India balked at this historical outreach attempt because it doesn’t want to share leadership of both countries’ shared peripheral region of Southeast Asia with China. Part of this has to do with the arrogance of the Modi-Doval Hindutva “deep state”, which truly believes that its “historical moment of greatness” has finally arrived and that it’s destined to hegemonically assert its power over the ASEAN countries which were influenced by its civilization millennia ago. The other related reason has to do with India’s elite overestimating their future potential and seriously believing that their country can one day compete with China.If New Delhi’s strategists, decision makers, and influencers were more soberly aware of India’s domestic shortcomings and international constraints, then they’d have instead welcomed the opportunity to build “Chindia” through BCIM rather than implicitly dismiss the project. The most mutually beneficial decision that India and China could make is to deepen their cooperation with one another via shared regional integrational platforms such as the BCIM, so it’s a major mistake for New Delhi to break with Beijing in stalling the project and dooming it to obscurity. The fact that both Asian Great Powers won’t be joining hands in collectively constructing a multipolar future for Eurasia and are poised to instead compete with one another for the Southeast Asian space between them is unfortunate, but it’s the American-desired reality which is setting in as a result of India’s inaction.BBINMore of a regionally focused plan than anything else, the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) Initiative aims to expand the road connectivity between all four states, and in theory it could also function as a stepping stone towards the construction of a Himalayan Silk Road linking China’s Tibet Autonomous Region with India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh via Nepal. That likely won’t happen anytime in the future for the reasons explained above in reference to the stalled nature of the BCIM, but it’s still a promising opportunity to bear in mind in the event that the leadership changes in New Delhi.Nevertheless, one would ordinarily be led to believe that all four parties would see some sort of multilateral benefit in the BBIN, and while that’s factually true, there are very real limits to one of its members’ cooperation on the project. Bhutan, to the surprise of many observers, bucked its historical trend of following India’s lead by declining to keep pace with BBIN’s integrational timeline because of the political opposition’s concerns that it could lead to irrevocable environmental damage to the pristine and largely untouched mountainous kingdom. With Bhutan basically out of the project for the foreseeable future, BBIN has been transformed into BIN and is even more constricted to India’s most immediate geographic neighborhood.BIMSTECThe final regional integrational project that India’s a part of (and which Bangladesh is a key component) is the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), and this initiative actually has somewhat of a chance to institutionally succeed. It was earlier written how India has decisively shifted its strategic focus eastward after having splitting up SAARC last year, and New Delhi’s main fallback plan was to develop BIMSTEC in lieu of SAARC. The motivation for this is obvious, and it’s that ASEAN members Myanmar and Thailand are a part of this grouping, and the organization’s Indian-led flagship project of the Trilateral Highway between all three aims to become the physical-commercial manifestation of Modi’s “Act East” policy.As it so happens, Bangladesh is literally the geographic focal point of BIMSTEC (hence the group’s Bay of Bengal name), which thereby makes the South Asian republic irreplaceably significant to India’s ASEAN-oriented plans. Without Dhaka’s active participation in this New Delhi-driven initiative and strategic subordination to its much larger neighbor, India won’t be able to secure the “Conflict Corridor” which stands between itself and Thailand. To explain, the broad swatch of territory stretching from the Indian state of Chhattisgarh to the eastern Myanmarese border is rife with numerous friction points for identity conflict (Hybrid War). Going from west to east, these include but aren’t limited to: the Naxalite insurgency; the potential for anti-center civil unrest in West Bengal; Bangladesh descending into Bangla-Daesh; rising anti-Bengali tensions in India’s Northeast; Bodo, Assamese, and Naga separatism in Northeast India; and the complex multisided Myanmarese civil war (which includes the “Rohingya” conflict).A strategic analysis of Indian-Bangladeshi relations will follow in the second part of the research, but at this concluding point it’s relevant to map out BIMSTEC and the “Conflict Corridor” in order to provide the reader with a clearer understanding of their interrelated significances, especially in terms of how Bangladesh fits into the entire framework. As can be seen from the map below, Bangladesh is indeed located right in the center of both of these concepts, and control over the country is correspondingly seen by India as the utmost priority for guaranteeing its international and domestic security for the reasons which will be expounded upon in the follow-up article.The article is continue-to read Part-II follow the link below.DISCLAIMER: The author writes for Regional Rapport in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

Bangladesh Is India’s Most Important Neighbor

India has sought to lead or co-chair four separate regional integration frameworks, all of which include Bangladesh, but only one of the plans has the full participation of each institutional member and any realistic chance of resulting in tangible multilateral benefits:

SAARC

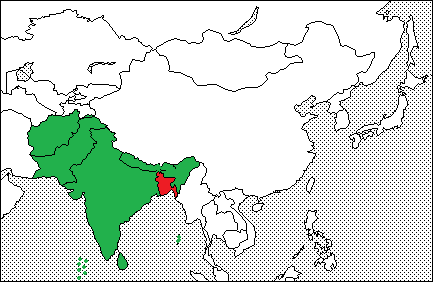

The South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) stretches from Afghanistan to Bangladesh and also includes the island nations of the Maldives and Sri Lanka. The idea behind it is innocent enough – to provide a platform of multifaceted integration between all of the former British colonies and one-time dependent territories to integrate with one another – but its execution has been utterly flawed due to India’s politicization of the organization as an instrument of international pressure against Pakistan. New Delhi sabotaged last year’s planned meeting in Islamabad by pressuring the other members to abstain from participating, though as the author wrote at the time, “India Just Split Up SAARC And Brought The New Cold War To South Asia”, but that “The Death Of SAARC Gave Birth To ‘Greater South Asia’”.

For all intents and purposes, so long as the ruling Modi-Doval Hindutva clique remains in control of India’s permanent military, intelligence, and diplomatic bureaucracies (the “deep state”), then there aren’t any realistic prospects for the SAARC format to return to being an apolitical vehicle for regional integration. Pakistan has accordingly prioritized its engagement with the Mideast and Central Asia in response, just as India has sought to do the same with ASEAN. As per the latter, New Delhi has three plans to fall back on, but only one of them has any feasible prospects for success nowadays.

BCIM

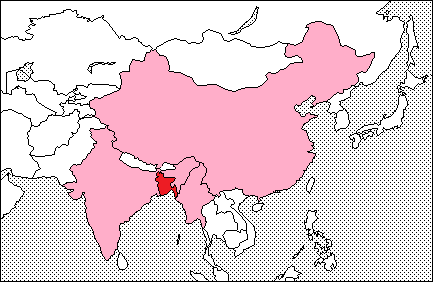

The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Corridor was supposed to be a grand cooperative undertaking between the world’s two most populous countries, China and India, but it’s regrettably underperformed in its vast potential due to New Delhi stalling the entire process. The Indians are overly afraid that China could flood their markets with all sorts of goods that would put their domestic producers out of business, hence why they prefer to keep the BCIM as more of a symbolic project than a substantial one. This has dissatisfied the Chinese, who genuinely want to bring together their and India’s economic complementarities in order to construct a win-win system of complex interdependency akin to the “Chimerica” concept.

India balked at this historical outreach attempt because it doesn’t want to share leadership of both countries’ shared peripheral region of Southeast Asia with China. Part of this has to do with the arrogance of the Modi-Doval Hindutva “deep state”, which truly believes that its “historical moment of greatness” has finally arrived and that it’s destined to hegemonically assert its power over the ASEAN countries which were influenced by its civilization millennia ago. The other related reason has to do with India’s elite overestimating their future potential and seriously believing that their country can one day compete with China.

If New Delhi’s strategists, decision makers, and influencers were more soberly aware of India’s domestic shortcomings and international constraints, then they’d have instead welcomed the opportunity to build “Chindia” through BCIM rather than implicitly dismiss the project. The most mutually beneficial decision that India and China could make is to deepen their cooperation with one another via shared regional integrational platforms such as the BCIM, so it’s a major mistake for New Delhi to break with Beijing in stalling the project and dooming it to obscurity. The fact that both Asian Great Powers won’t be joining hands in collectively constructing a multipolar future for Eurasia and are poised to instead compete with one another for the Southeast Asian space between them is unfortunate, but it’s the American-desired reality which is setting in as a result of India’s inaction.

BBIN

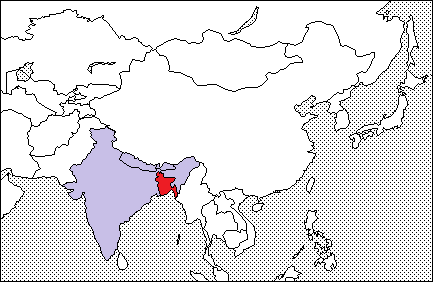

More of a regionally focused plan than anything else, the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) Initiative aims to expand the road connectivity between all four states, and in theory it could also function as a stepping stone towards the construction of a Himalayan Silk Road linking China’s Tibet Autonomous Region with India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh via Nepal. That likely won’t happen anytime in the future for the reasons explained above in reference to the stalled nature of the BCIM, but it’s still a promising opportunity to bear in mind in the event that the leadership changes in New Delhi.

Nevertheless, one would ordinarily be led to believe that all four parties would see some sort of multilateral benefit in the BBIN, and while that’s factually true, there are very real limits to one of its members’ cooperation on the project. Bhutan, to the surprise of many observers, bucked its historical trend of following India’s lead by declining to keep pace with BBIN’s integrational timeline because of the political opposition’s concerns that it could lead to irrevocable environmental damage to the pristine and largely untouched mountainous kingdom. With Bhutan basically out of the project for the foreseeable future, BBIN has been transformed into BIN and is even more constricted to India’s most immediate geographic neighborhood.

BIMSTEC

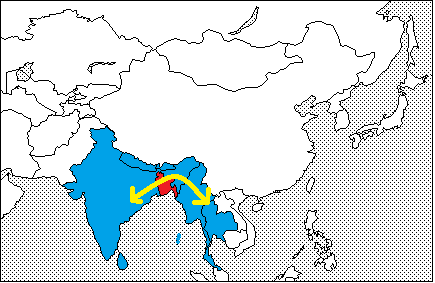

The final regional integrational project that India’s a part of (and which Bangladesh is a key component) is the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), and this initiative actually has somewhat of a chance to institutionally succeed. It was earlier written how India has decisively shifted its strategic focus eastward after having splitting up SAARC last year, and New Delhi’s main fallback plan was to develop BIMSTEC in lieu of SAARC. The motivation for this is obvious, and it’s that ASEAN members Myanmar and Thailand are a part of this grouping, and the organization’s Indian-led flagship project of the Trilateral Highway between all three aims to become the physical-commercial manifestation of Modi’s “Act East” policy.

As it so happens, Bangladesh is literally the geographic focal point of BIMSTEC (hence the group’s Bay of Bengal name), which thereby makes the South Asian republic irreplaceably significant to India’s ASEAN-oriented plans. Without Dhaka’s active participation in this New Delhi-driven initiative and strategic subordination to its much larger neighbor, India won’t be able to secure the “Conflict Corridor” which stands between itself and Thailand. To explain, the broad swatch of territory stretching from the Indian state of Chhattisgarh to the eastern Myanmarese border is rife with numerous friction points for identity conflict (Hybrid War). Going from west to east, these include but aren’t limited to: the Naxalite insurgency; the potential for anti-center civil unrest in West Bengal; Bangladesh descending into Bangla-Daesh; rising anti-Bengali tensions in India’s Northeast; Bodo, Assamese, and Naga separatism in Northeast India; and the complex multisided Myanmarese civil war (which includes the “Rohingya” conflict).

A strategic analysis of Indian-Bangladeshi relations will follow in the second part of the research, but at this concluding point it’s relevant to map out BIMSTEC and the “Conflict Corridor” in order to provide the reader with a clearer understanding of their interrelated significances, especially in terms of how Bangladesh fits into the entire framework. As can be seen from the map below, Bangladesh is indeed located right in the center of both of these concepts, and control over the country is correspondingly seen by India as the utmost priority for guaranteeing its international and domestic security for the reasons which will be expounded upon in the follow-up article.

The article is continue-to read Part-II follow the link below.

http://regionalrapport.com/2017/05/12/bangladeshs-breakout-plan/